Alexander Pope believed that the life of human beings and the life of books are intimately connected. Good literature has the power to elevate and improve us, while literature that is either irrelevant or poorly written may injure us.

To read well is to receive what some theologians name gratia communis—a goodness which sustains the true, the good, and the beautiful in the world. The value of literature is known well enough to anyone who has enjoyed a good story. When pressed to justify the humanities, professionals often acknowledge the moral effect of literature, especially its capacity to exercise empathy. Literature does more than simply make us more empathetic. It dilates our moral capacity, enriches our enjoyment of life, sharpens our attention, and enlarges our ability to communicate, solve problems, celebrate, lament communally, and to imagine a more just society.

But the gifts of good literature depend upon how we read. Today’s visual iconography regulates our attention with accelerated stimulation. Digital entertainment is the new speed that allows one to circumvent experience. As the poet Jorie Graham said in a recent interview, “Speed allows you to bypass experience and that is probably the greatest desire of humans right now, that is, not to be touched by experience and just to be able to grasp, laugh, and to be entertained quickly.”

“Slow reading” is perhaps the best antidote against short-form, quick entertainment. In his 1959 essay “Reading in Slow Motion,” Reuben A. Brower promoted a method of reading that involved “slowing down the process of reading to observe what is happening, in order to attend very closely to the words, their uses, and their meaning.” This process of reading in slow motion requires us to cultivate “the complete and agile response to words that is demanded by a good poem.”

To rush, to read passively, is to risk missing the beauty before it discloses itself.

Literature requires the surrender of our time and imagination through the promise of gradual and lasting gratification, initiated the moment we behold the white interval between the first chapter heading and its first sentence. It continues long after we’ve closed the book. This is especially true for works of the imagination, e.g., poetry, novels, drama, although each will demand a different kind of agility.

Great works of literature are lived with. In the spirit of Brower’s experiment, the method of slow reading I practice in my classrooms and online courses is one of companionship, a prolonged encounter with a text in which meaning is discovered by degrees, recursively. This kind of reading is out of step with our age, and that is its virtue. It asks for time, for patience, and for surrender.

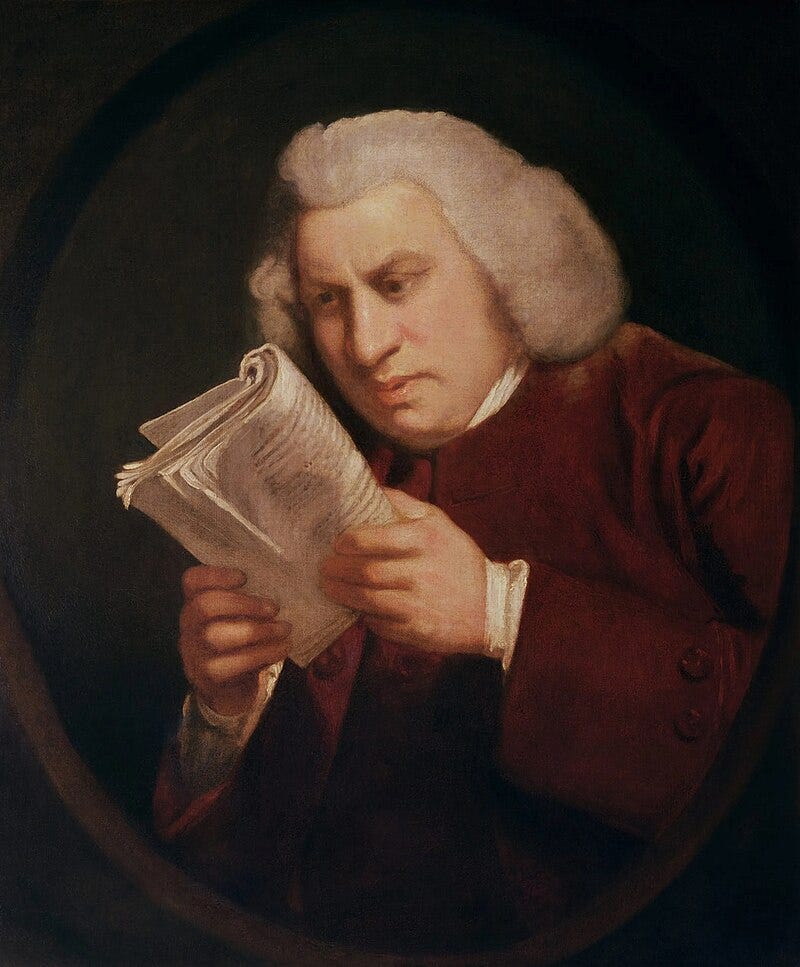

Such works, as Samuel Johnson wrote, have the “power of attracting and detaining the attention,” great works “whose pages are perused with eagerness, and in hope of new pleasure are perused again; and whose conclusion is perceived with an eye of sorrow, such as the traveler casts upon departing day” (Johnson, “Life of Dryden”).

The recursive discovery described here applies beautifully to re-reading too. Great books seem to grow alongside us, offering new insights with each return visit.

Wise words. I read Brower’s essay last year because you mentioned it and it definitely changed my relationship with literature. I think most people need to learn how to appreciate things in themselves; reading just for the sake of reading